The president has taken risks that were not well received by investors and foreign governments, such as making Bitcoin legal tender.

Phillip Euell does not hide his enthusiasm when he talks about his upcoming trip to El Salvador’s capital, San Salvador. This American citizen went from being a Bitcoin fan to practicing as a lawyer in cryptocurrency insolvency cases, and this experience in the only country in the world that has made Bitcoin legal tender is an obvious competitive advantage for him.

“I would love to have clients in El Salvador and I am working on that,” he says in a video call from the office of his firm Diaz Reus in Miami, “I know some Americans who live there and they say that being there now, compared to a few years ago, is really different, since the security situation has improved dramatically. Now the second big obstacle is economic.”

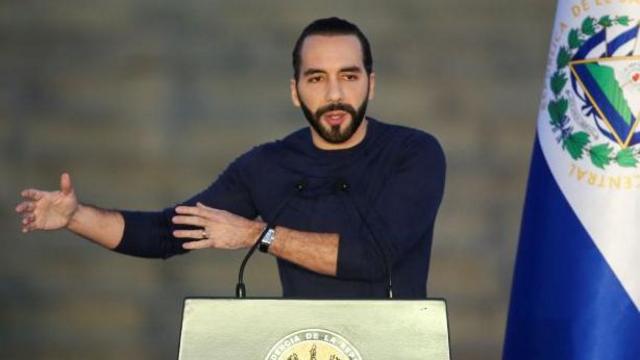

Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele won the presidential election earlier this year and will remain in charge for at least another four years. In the first four years as president, he focused on the so-called “war on gangs,” through which he managed to significantly reduce violence and crime in general, with methods widely criticized for violating human rights. But in the world of big capital, trust and security translates into a better business environment and this is what Bukele is seeking to create now. If law and order was the first obstacle to overcome, the economy will be the second.

It will not be easy to achieve it and, in part, it is because Bukele himself has taken some risks that were not well received by investors and even governments abroad. In September 2021, the Bitcoin Law was passed with the idea that citizens could use the digital asset as currency to pay for everything from real estate to street food. This did not work, according to central bank data, which indicates that Bitcoin is only marginally used within the country.

Bukele also invested parts of the country’s financial reserves in Bitcoin, a risky bet for bondholders listed on the international market. When Bitcoin fell in price, it was rumored that El Salvador would default on its debt. Today, with the price of the asset skyrocketing, it is estimated that the Central American country’s international reserves have increased in value by 62% since the purchases were made. For now, this is a success, but the pro-cryptocurrency legislation has not translated into more foreign investment.

For 30 years, El Salvador has been lagging in attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) compared to its peers in emerging markets. “This is attributed in part to extortion and widespread gang-related crime,” says an annual report on the country from the US State Department, “security improvements have not yet translated into significant new FDI and it is currently unclear how the government will end the State of Exception and restore the constitutional rights.”

However, the U.S. government warns, the state of emergency enjoys broad public support “and is contributing to improving consumer confidence and optimism about economic conditions.” That is, if there was a time for Bukele to capitalize on his achievement, that time is now. The Administration has planned several large infrastructure projects and the U.S. government has identified them as potential opportunities for its companies. Projects include improving road connectivity and logistics, expanding airport capacity, and improving access to water and energy, as well as sanitation. Given the limited fiscal capacity for public investment, the Salvadoran government seeks to use public-private partnerships (PPP) for infrastructure projects.

Bukele decided to go into debt aggressively in 2020, less than a year after taking power, to transfer direct support to the population during the Covid-19 pandemic. This led to a debt level close to 70% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), according to data from the rating agency S&P Global. The firm improved the rating of Salvadoran sovereign bonds at the end of last year after the government managed to refinance its domestic debt in negotiations with national banks, although it still maintains it at a level considered “speculative” and far from investment grade.

“Despite the fiscal relief that it derives from these measures, the country’s public finances remain fragile,” S&P analysts Patricio Vimberg and Omar De la Torre wrote in their report. “El Salvador’s rating includes institutional weaknesses, as indicated by long-standing difficulties in forecasting policy responses in a context of poor checks and balances, a modest GDP per capita of $5,200, and moderate GDP growth expectations due to persistently low investment and productivity.”

The government has been in talks with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which could be a more flexible and less expensive source of financing. For the Fund, the low use of Bitcoin as legal tender could represent a greater probability of lending money to the Central American country since it mitigates the risks of its exposure to price fluctuations. S&P considers it possible that an agreement will be reached between El Salvador and the IMF this year.

Bukele’s economic gamble is on the combination of these two factors, law and order and cryptocurrencies, says Cory Klippsten, executive director of Swan, a bitcoin financial services company based in Los Angeles. “The promotion of Bitcoin seems to be part of the marketing push and certainly seems to be improving things in many areas, particularly in the security to attract foreign investment,” says the businessman.

“There are a lot of people going there, buying real estate, developing beachfront homes and condos and thinking about opening businesses in San Salvador,” Klippsten adds, “there is a resurgence of interest in country clubs and things like that around San Salvador, and a lot of those people are in and around the bitcoin space. They are fans and believers.”

Euell, the lawyer, agrees: “It is difficult to make an economy grow and inspire confidence, one that works and has positive rates of growth. I think there is a lot of work ahead, but people are excited.” (https://english.elpais.com/international/2024-04-03/after-fixing-el-salvadors-gang-problem-nayib-bukele-sets-his-sights-on-the-economy.html)

Presidential terms in El Salvador are (still) five years, not four years.