Concern over China’s economic clout has created “a hell of a chance” for the US to pass legislation paving the way for more free trade deals with Latin American countries, said President Joe Biden’s special adviser for the region.

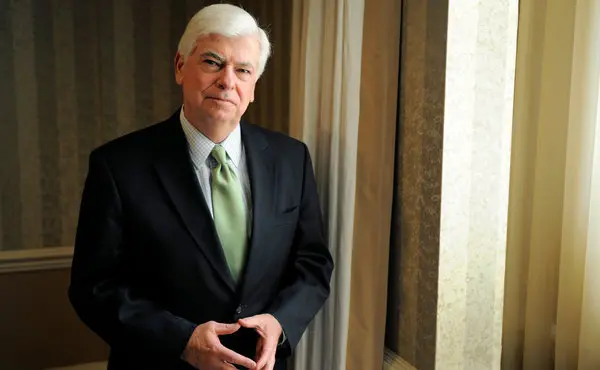

Former senator Chris Dodd said he was increasingly optimistic about the Americas Act getting through Congress this year — which would harmonize and expand existing US trade deals with Latin American nations and offer incentives to “nearshore” production from China.

“We’d love to see the Americas Act passed,” Dodd told the Financial Times on the sidelines of the Concordia Americas summit in Miami this week.

Asked about the bill’s chances in an election year, he said: “If you’d asked me that question any other time, I would say ‘not much’, but in this environment, it has got a hell of a chance. You’ve got a bipartisan, bicameral proposal from people who are highly regarded and respected.”

China has vastly expanded trade and investment in Latin America this century, displacing the US as the region’s biggest trading partner. That has triggered worries in Washington that it is losing clout in an area traditionally under its sway.

But the US has lacked the tools to fight back after years of congressional opposition to expanding free trade.

However, legislators in both houses introduced the bill in March with bipartisan support. The Global Americans think-tank described the Americas Act as “the most comprehensive US policy attempt to deepen relations with the Western Hemisphere in more than two decades”.

The bill represents an attempt to turn back towards the ambitious vision touted in the 1990s by presidents George HW Bush and Bill Clinton of a free trade area stretching from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego.

That dream died as opposition from leftwing Latin American governments in the first years of this century torpedoed the talks, prompting Washington to shift towards individual country deals.

Today the US has a patchwork of trade pacts with 12 nations in the Americas. The US-Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) is by far the most important, while Central America and the Dominican Republic have their own pact.

Brazil and Argentina, the region’s largest and third-largest economies, respectively, have no free trade agreements with the US.

Dodd said worries about China’s growing economic power in Latin America “certainly contributed” towards the change of congressional mood in Washington over trade and investment.

The Americas Act would require participating countries to sign up to standards on democracy and the rule of law as well as trade. It establishes a potential process for countries to join USMCA, with Uruguay and Costa Rica seen as ideal initial candidates.

Dodd said if US trade and investment incentives were attractive, the package could be offered to any country willing to accept the conditions.

“If you can get economic growth occurring even in Venezuela, then you will avoid the next 25 years of another Cuba and 8 mn Venezuelan [migrants] in Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador, and the United States,” he said.

The US eased tight economic sanctions on Venezuela in October in an attempt to encourage moves toward free and fair elections. That gesture was partially reversed this month as Washington said Caracas had “fallen short” of its promises.

Dodd quoted Biden as telling Colombia’s leftwing President Gustavo Petro at the White House last year “I hate sanctions as the president of the United States. I think they’re dreadful. I don’t think they work.

“I think they’re painful to people and I’m willing to get rid of them in Venezuela but it’s going to be tit for tat. . . [if] Venezuela does certain things, I will start to pull [sanctions] out.” Petro was “blown away”, Dodd recalled. (https://www.ft.com/content/e113f911-542e-44c8-83e0-bedb4798875f)